Anxious Mums author, Dr Jodi Richardson, offers advice for mothers and children experiencing anxiety.

One in four people will experience anxiety within their lifetime, making it the most prevalent mental health condition in Australia. Statistics determine it is twice as common in women, with one in three, compared with one in five men, diagnosed on average.

Having lived and studied anxiety, Dr Jodi Richardson is an expert in her field, with more than 25 years of practice. In addition to her professional background, it was ultimately her personal experiences and journey in becoming a mother that shaped the work she is passionate about.

Jodi’s books, Anxious Kids; How Children Can Turn Their Anxiety Into Resilience, co-written with Michael Grose (2019), and her latest release, Anxious Mums; How Mums Can Turn Their Anxiety Into Strength (2020), offer parents, in particular mothers, advice on how to manage and minimalise anxiety, so they can maximise their potential, elevate their health and maintain their wellbeing.

The more I learned about anxiety, the more important it was to share what I was learning.”

Jodi’s first-hand experiences have inspired her work today, stating, “The more I learned about anxiety, the more important it was to share what I was learning.”

Jodi’s first signs of experiencing anxiety appeared at the early age of four. Her first symptoms began in prep, experiencing an upset stomach each day. Her class of 52 students, managed by two teachers, was stressful enough, on top of her everyday battles. Jodi recalls, “There was a lot of yelling and it wasn’t a very relaxing or peaceful environment, it obviously triggered anxiety in me, I have a genetic predisposition towards it, as it runs in my family.”

Twenty years later, the death of a family member triggered a major clinical depression for Jodi. She began seeking treatment however, it was in finding an amazing psychologist, that helped her to identify she was battling an underlying anxiety disorder. Jodi discloses, “It was recognised that I had undiagnosed anxiety. I didn’t really know that what I had experienced all my life up until that point had been any sort of disorder, that was just my temperament and personality.”

After many years of seeing her psychologist, Jodi eventually weaned off her medication and managed her anxiety with exercise and meditation. Offering advice on finding the right psychologist Jodi states, “For me it was my third that was the right fit. I really encourage anyone if the psychologist you were referred to doesn’t feel like the right fit, then they’re not and it’s time to go back to your GP. Having the right professional that you’re talking to and having a good relationship with is really important for the therapeutic relationship.”

Jodi highlights the importance of prioritising mental wellbeing, affirming, “The more we can open up and talk about our journeys, the more we encourage other people to do the same and normalise the experience.”

Anxious Mums came into fruition after a mum in the audience of one of Jodi’s speaking engagements emailed Jodi’s publisher stating, “Jodi has to write a book, all mums have to hear what she has to say.”

Anxious Mums came into fruition after a mum in the audience of one of Jodi’s speaking engagements emailed Jodi’s publisher stating, “Jodi has to write a book, all mums have to hear what she has to say.”

Everyday efforts new mothers face, consign extra pressure on wellbeing and showcase the need to counteract anxiety before it subordinates everyday lifestyles. While Jodi’s children are now early adolescents, she reflects upon the early stages of new motherhood, “Ultimately when I became a mum with all the extra uncertainty and responsibility, as well as lack of sleep, my mental health really declined to a point where I ended up deciding to take medication, which was ultimately life changing.”

When I became a mum with all the extra uncertainty and responsibility, as well as lack of sleep, my mental health really declined to a point where I ended up deciding to take medication, which was ultimately life changing.”

New mothers experience heightened anxiety as they approach multiple challenges of parenthood; from conceiving, through the journey of pregnancy, birth and perpetually, thereafter. Becoming a mother provided Jodi with insight into new challenges, in particular struggles with breastfeeding and lack of sleep. She shares, “It’s something that we don’t have much control over, particularly as new parents. We just kind of get used to operating on a lot less sleep and it doesn’t serve us well in terms of our mental health, particularly if there have been challenges in the past or a pre-existing disorder.

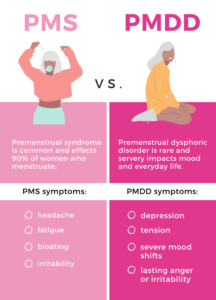

Research suggests women’s brains process stress differently to men, with testosterone also said to be somewhat protective against anxiety. This, along with different coping mechanisms of women, highlight statistic disparity between gender. For early mothers in particular, it is a time of immense change, as their everyday lives are turned upside down. New schedules, accountability and hormonal changes increase the likelihood of anxiety and depression, which are also commonly triggered in the postpartum period.

Jodi elaborates on important hormonal timeframes that shift women’s mental wellbeing stating, “Anxiety is heightened during times of hormonal changes as well as in the key points in our reproductive lives. Through having children and menopause and alike. It’s more disabling in that it impacts our lives in different ways to men, particularly I think, because we’re usually the main carers. There are stay at home dads, but predominantly that’s what women tend to do.”

Normal anxiety is infrequent and settles down, but when someone suffers a disorder, they can have incessant worry and avoidance. This can include anxiety around not wanting to participate, attend a function, for example, try something new or step up in a work role. Anxiety disorders can be crippling, leaving sufferers feeling as though they are unable to live their best life.

There’s no harm in going and asking the question because the gap between the first symptoms of anxiety and seeking help is still eight years in Australia.”

There are many telling physical signs and symptoms of an anxiety disorder. Some indicative signs to look out for include a racing heart, trembling, sick stomach, frequent perspiration and dizziness that accompanies shortness of breath. Jodi says, “If you think that your anxiety might be a problem, that’s absolutely the time to go and make an appointment to see your GP. There’s no harm in going and asking the question because the gap between the first symptoms of anxiety and seeking help is still eight years in Australia.”

“Half of all mental illness comes on by around the ages of fourteen. Most adults who have anxiety can track it back to when they were teenagers or children.”

Just as anxiety is common for mothers, it’s also important to observe and be aware of in children. Jodi reveals, “For parents it’s important to know that half of all mental illness comes on by around the age of fourteen. Most adults who have anxiety can track it back to when they were teenagers or children. 75 percent of all mental illness comes on by about the age of 25, with one in seven children [4-17 years old] being diagnosed with a mental illness, and half of those have anxiety.”

“75 percent of all mental illness comes on by about the age of 25, with one in seven children [4-17 years old] being diagnosed with a mental illness, and half of those have anxiety

These pre-covid statistics highlight significant numbers of anxiety in adolescents. However, with the current climate prevalent of immense loss of control, many are facing new heightened emotions and increased numbers of anxiety. Early research coming out of Monash University is showcasing significant growth of adults with depression and anxiety, including statistics of children in the early ages of one to five experiencing symptoms.

Similar research has given light to evidence portraying children mirroring stress responses of their parents. Jodi further explains, “They can pick up the changes in our own heart rate, in our stress response — we are told that as new mums aren’t we, that our babies can pick up on how we are feeling but the science proves that to be true as well.” Parenting is a consequential way in which children receive cognitive biases and behaviours, “Just the tone of our voice, the expressions on our face, the way that we speak, what we say, certainly can be picked up on by kids and mirrored back.”

Noticing these early signs in your children is essential to alleviating anxiety before it progresses, Jodi lists some signs to be aware of, “Avoidance is a hallmark sign of anxiety — I don’t want to go, I don’t want to participate, I don’t want to deliver that oral presentation in class, I don’t want to go to camp and so watching out for that sort of thing. Other signs and symptoms to look out for include big emotions. If your children seem more teary or angry than usual, are feeling worried or avoidant, can’t concentrate, having trouble remembering or difficulty sleeping.” It’s important to be aware and help counteract anxiety when you see it.

Jodi offers parents, who are struggling coping with their children’s anxiety some advice stating, “It’s an age old question, how much do we push and when do we hold back; I think as parents we are constantly answering that question. We don’t always get it right, but the thing about avoidance is it only makes anxiety worse. So for the child who is anxious about going to school, the more they stay home, the harder it will be to front up on another day. Sometimes, we need to nudge them forward in small steps and that’s a technique called step-laddering. It’s about making a step in that direction.”

Jodi encourages parents to observe their children’s symptoms and to never feel ashamed to go see a GP. She urges, “Sometimes we get that reassurance from a GP, it might just be developmental, but the sooner kids are getting the help they need, the better, and it’s the same for us as mums.”

There are simple everyday steps we can take to combat anxiety. When someone is anxious a threat has been detected within the brain, this part of the brain is called the amygdala, one of the most powerful strategies for managing this stress detection is regulant meditation.

Jodi explains, “What meditation does is it brings our attention to the present, so we are paying attention to what’s happening in the moment.” Meditation recognises deliberate breathing with a focus equally on exhalation as inhalation, proven to be calming to the anxious brain, using the relaxation response.

Commending the importance of the practice and its effect on functioning, Jodi describes, “Meditation is more that sort of seated and formal practice of focusing the breath. What we know this will do over time, is it reduces the size and sensitivity of the amygdala, so it’s less sensitive to threat which reduces long-term anxiety. For the average person, our minds wander around 50 percent of the time, when we can bring our attention back to the present we are much more likely to be able to settle our anxiety, and feel happier as well.”

Another everyday strategy for combatting anxiety is exercise. Jodi shares her experience and routine stating, “Exercise is something I’ve used my whole life to calm my anxiety. Even now, I do cross-fit, karate and walks every week. I think naturally I was managing my health and wellbeing without really understanding why, I just knew that it made me feel good.”

The fight or flight response tied to anxiety powers us up to fight physically to save our lives or to flee. So often, when someone is anxious, they are powered up in this way, but not doing anything about it. Jodi shares, “When we move, it’s the natural end to the fight or flight response. Not only that, when we exercise we release serotonin, which is a feel good neural transmitter, among with gamma aminobutyric acid, a neural transmitter that puts the breaks on our anxiety response helping to calm us down.”

Jodi’s practice in physiology, working with clients using exercise to help them with their mental and physical health has led her to her understandings, “One of the things I can 100 percent tell you is that it’s best not to wait until you feel motivated — the motivation will come once you get into the routine of it.

I’d just like to say, anxiety isn’t something we need to get rid of to really be able to thrive, to do what we need to do and accomplish what’s important to us. But I really encourage to anyone, that there are lots of ways to dial it back. I think it’s very easy for us to wait until we feel 100 percent to do something, but doing anything meaningful is hard.

So don’t wait until your anxiety is gone because you might be waiting a long time.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help now, call triple zero (000)

Lifeline: Provides 24-hour crisis counselling, support groups and suicide prevention services. Call 13 11 14, text on 0477 13 11 14 (12pm to midnight AEST) or chat online.

Beyond Blue: Aims to increase awareness of depression and anxiety and reduce stigma. Call 1300 22 4636, 24 hours/7 days a week, chat online or email.

Kids Helpline: : Is Australia’s only free 24/7 confidential and private counselling service specifically for children and young people aged 5 – 25. Call 1800 55 1800

To learn more about Dr Jodi Richardson’s work, watch the full interview below or on our YouTube channel.

I promise you’ll feel better. Fresh air is good for your mood and your soul, especially if it’s nice and sunny. Let the kids run and burn some energy. Move your body and breathe in the day. Bonus points if you can sit outside to meditate.

I promise you’ll feel better. Fresh air is good for your mood and your soul, especially if it’s nice and sunny. Let the kids run and burn some energy. Move your body and breathe in the day. Bonus points if you can sit outside to meditate.