The adoption process is not easy, but for some parents adoption it is their last chance at a family.

After 10 years of In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) treatments, plus two and a half years of waiting in the adoption program, hairdresser Pina and her husband John were finally able to have that chance.

The Melbourne couple, are one of the lucky sets of parents who were able to adopt a baby boy 20 years ago. Both had wanted children since their mid to late-twenties and after exhausting all their options to have their own biological child, they turned to adoption.

The 10 years of IVF treatments had taken their toll on Pina physically and mentally, seeing her future continuously taken away from her, made her feel like the adoption process would be just another form of torture and in some respects it was.

Still, she felt she had nothing to lose and if IVF had taught her anything, it was that she was willing to risk it. Thankfully, luck was on her side and after 13 years of waiting, Pina and John welcomed a baby boy into their family.

Pina explains how the IVF treatments hurt her. “We kept making beautiful embryos, through IVF,” Pina shares.

“For whatever reason, they never stuck to me. However, I think there is a reason in life, why things happen – I was meant to have Damien.”

IVF is an intrusive procedure that has a success rate per fresh embryo transfer of 38.8% for live birth and 44.9% for clinical pregnancy (ages 18-34) and 32.2% (live birth), 41.7% (clinical pregnancy) for ages 35-38, ages greater than 38 it drops even further.

“They kept saying to me that there is absolutely nothing wrong, my husband had the low sperm count that’s the reason we went on it. As the woman, I had to go through a lot,” Pina recalls.

I was at the point where I thought, I’m not meant to have kids and that’s it, end of story.” It was then, Pina’s husband, John mentioned adoption.

Although adoption seems like a great back-up plan for a family, in reality, it’s a very complex system with the average wait time being between five and seven, if one passes the qualifying stages. Between 2018-2019 there was a total of 310 adoptions Australia wide, 82% were Australian born children and 67% of the 310 adoptions were from their foster parents.

With the increase in women’s rights and family planning and the resulting drop of children in the adoption system, means there are more parents waiting to adopt than there are children needing to be adopted.

Australia’s adoption policies differ depending on the States. In Victoria there are three kinds of adoption systems: local adoption, inter-country adoption and permanent care.

There are also only 13 partner countries with Australia for adopting children, each having independent rules and regulations which can restrict options. Factors such as being married, single, male or female, in a de-facto relationship, one’s age, gender orientation and sexuality can all affect one’s chances of adoption.

The local adoption requirements are less strict, for example a persons’ orientation or relationship status does not matter but there is a demanding application process which examines a person’s life in minute detail.

The biological parents learn everything about the adopting parents as well has gaining many rights, one of which is the right to visitation.

Even though we would be adopting their children, they still get to see them,” Pina says.

Pina didn’t have a problem with this requirement because she believes it’s important for a child, any person for that matter, to know their heritage to better understand oneself.

To be qualified and placed in the adoption program would take two years for Pina and John. As Pina says, “They wanted to get to know us better than we knew ourselves.”

Answering endless questions fuelled a gruelling and extensive qualification process. It was also yet another period of trying not to get their hopes up in fear of disappointment.

The final step, after 2.5 years of the application process, was an intimidating interview with a panel of lawyers, doctors, psychologists and Department of Human Services (DHS) staff.

Pina says she thought they were successful because of her view of it not mattering to her who or where the child was from, to her a child was a child and if she could supply the home then she would gladly do it.

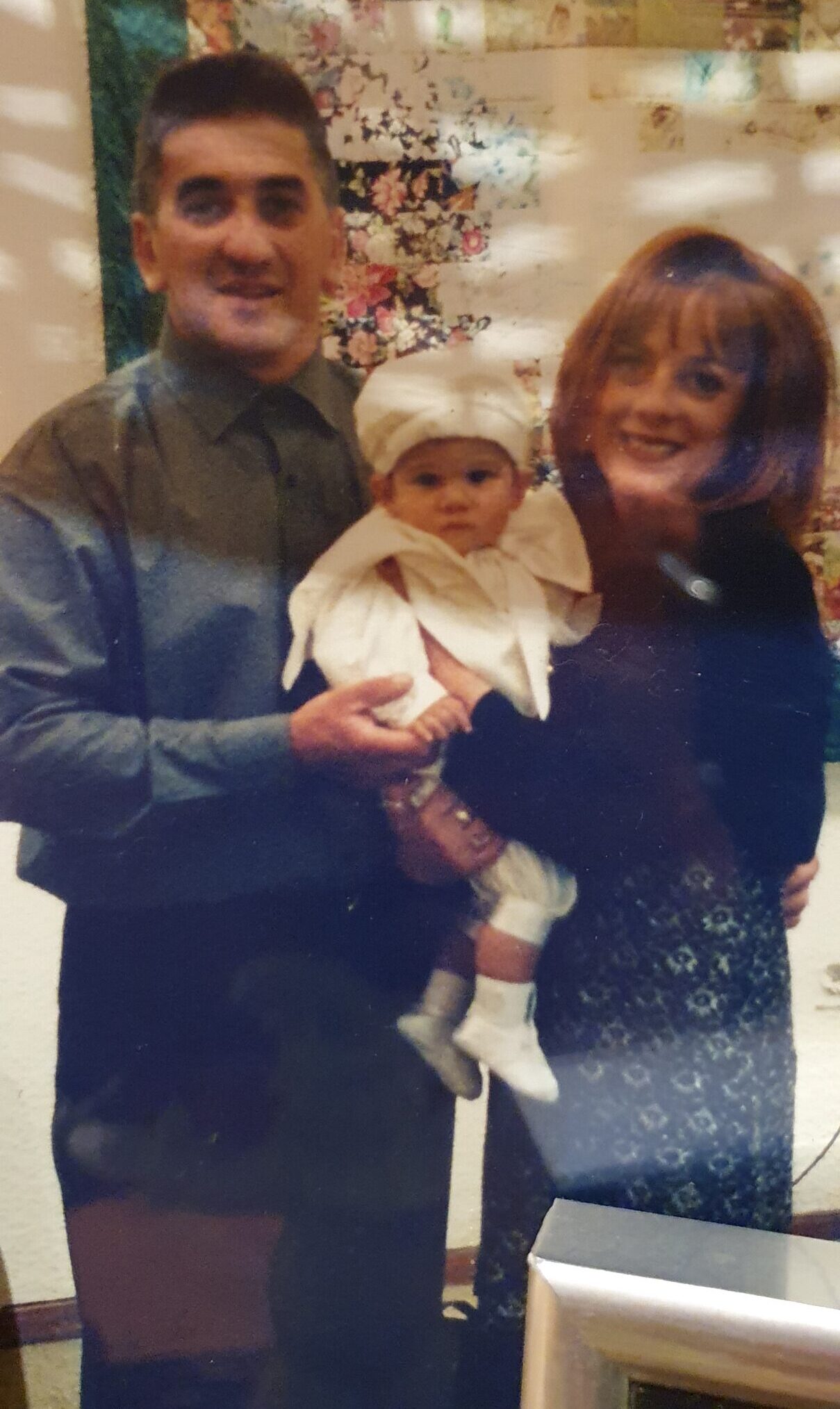

Two months later, they got the call that they were to be the parents of a 4.5-month-old baby boy, whom they named Damien.

The first time I lay eyes on him, I just thought he was the most beautiful little baby ever,” Pina recalls.

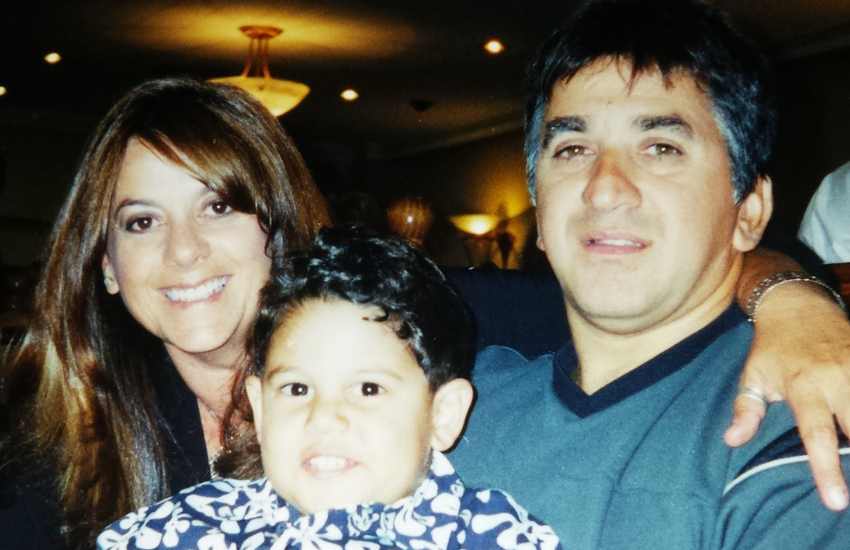

However, their adoption story did not end there, it has always been in the background through Damien’s childhood, adolescence and even into adulthood.

Damien has known he was adopted from an early age. Pina took the approach to start filling him in as soon as he could understand.

Pina strongly wanted Damien never to question where he belonged, she made sure he knew he was a part of this family and nothing could change it.

I told him little bits and pieces and as he got older,” Pina says.

“He knows that he has biological siblings, and yes that was a bit hard, I did not know how he would take it. I suppose growing up he knew nothing other than us; we are his parents- this is his family. He never really questioned it and had no interest in meeting her (his biological mother) or his siblings.”

Although Damien never questioned who he was and where he belonged it was still difficult to understand why his biological mother gave him up, especially when she had children already.

Even though Damien’s biological mother hardly used the visitation rights, as she wanted a clean break, she has been in contact with Damien over the past 20 years.

In some ways it was more detrimental than good for Damien. Each time would raise his expectations, to have some sort of relationship and understanding, only to be rejected all over again.

Damien does not know who his biological father is, although he knows it is where he gets his aboriginal heritage. While having no information on the biological father has been challenging in having real access to the Australian Indigenous community for Damien, both Pina and John made sure he was in touch with his cultural heritage.

“Adoption is a gamble. Any child is a gamble. Whether you adopt or whether you have one biologically. They can grow up to be the best, they can grow up to be the worst they can grow up to be anything,” Pina explains.

It has nothing to do with whether you gave birth or not. In the end it’s all the same.”

Adoption and its process are not for the feint hearted but if fate is on side it’s the best chance at having a family.