As a child who fought more with her two imaginary friends than laughed, I reflect on how real it was for those around me.

“Alright, that’s it!

Tom and Ellie get out of the car now, you’re not coming back home,” I remember my mum yelling.

It was a casual afternoon in mid-2001, I was two-and-a-half years old and the back seat of our forest green Subaru was filled with three children fighting over the last Twistie. I kicked and screamed, not happy with the designated chip outcome, begging the other children to give it to me.

However, I was the only physical child in the back seat. Tom and Ellie were “invisible” fragments of my imagination. Invisible fragments that I fought with so much, I forced Mum to throw them away.

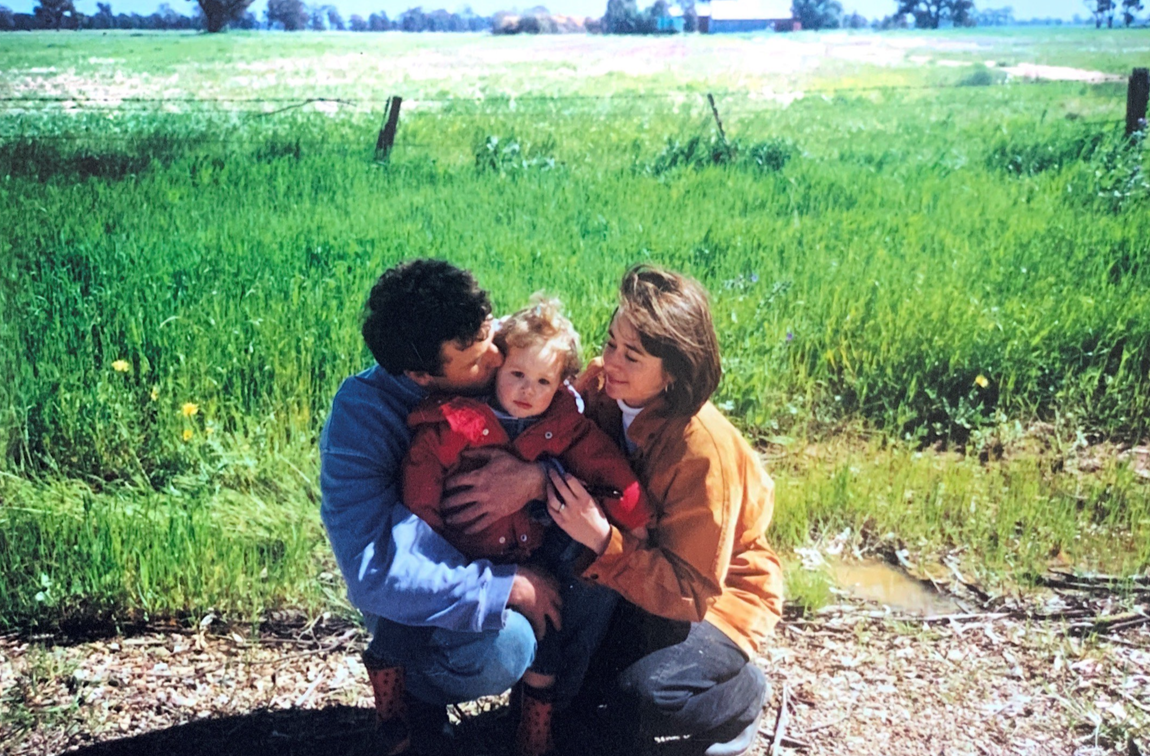

This day was the tip of the iceberg for my mum, feeling like she was the mother to triplets instead of just me. Throwing these “friends” out of the car seemed like the only way to keep the peace and her sanity intact. She was beyond patient with my constant demands. Making sure these unseen beings were properly bathed, dressed, fed and securely buckled into the car before leaving home.

“It was really draining,” says Mum, when asked to reminisce on this stage of my childhood.

“I would have to give everyone a bath each night and when told I didn’t dry them properly, the process had to start all over again.

“As a mum, I knew it was my responsibility to remove a problem that was so obviously agitating my daughter, so ultimately that is what made me stop the car that day.”

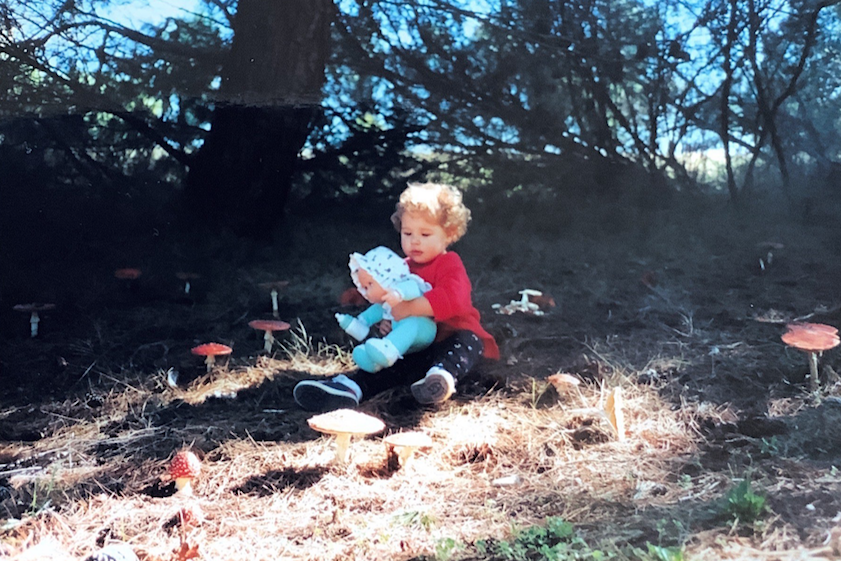

Fast forward to the present and I cannot tell you what Tom and Ellie looked like, but when I was a child, they were so vivid within my imagination. They kept me company, forcing me to explore social situations at such an early age. There were plenty of times the three of us were the best of friends, but unfortunately, the fighting outweighed the calm. I knew the playmates I was bickering with over toys, food and personal space were fictional characters within this chapter of my life, however, they were still emotionally and intellectually alive.

My make-believe friends were most likely born out of boredom or the fundamental desire for company, as Tom and Ellie emerged into my life before my little sister was born. Even though we all drove mum crazy, these beings allowed my parents to gain an insight into the creations of my inner world. They noticed what made me shriek with both laughter and anger, my likes, dislikes and inventiveness.

Mum worried I had psychological problems or was meant to be a triplet and had separation anxiety. However, with copious research, she discovered having imaginary friends was a normal part of growing up and developing.

Studies show that imaginary friends are an extremely natural and healthy part of a child’s development. Up to two-thirds of children create make-believe playmates, usually between the ages of three and eight. Dr Psych Mum says these friends are more common amongst firstborn or only children, as they satisfy the need for friendship and companionship, notions in which many only children crave.

The stigma surrounding imaginary friends used to be harsh. Up until the 1990s, people believed they were a psychological red flag, being a sign of loneliness within the child or a reluctance to accept reality. Others also thought these invisible companions were a sign of an evil demonic possession or early signs of mental illness.

However, developmental psychologist Marjorie Taylor said in an interview with The Globe and Mail, that children who manifest these beings grow up to be creative adults, with further links to higher developed social and verbal skills.

Psychologists from all around the world agree children with imaginary confidants – whether that be friends or personified objects – tend to engage more with their peers as they grow up. They also found that these children are more advanced in knowing how to react with imagining how someone else might think and behave in certain situations.

The inclusion of pretend friends within a child’s life fulfils three fundamental psychological needs: competence, relatedness and autonomy. Competence is met by the child assuming a leadership role towards the imaginary friend, an established invisible hierarchy. Relatedness is accomplished by teaching a child ways to connect socially with real-life human beings as they grow older. Autonomy is satisfied by a child gaining a sense of control over their parents, by demanding they complete tasks for their companion.

Imaginary friends inspire children to explore their curiosity in a make-believe world they constructed within their own minds. They provide a sense of comfort, freedom for life lessons and learning curves in the real world.

Looking back and laughing with Mum over these crazy antics with my treasured friends, I am grateful my two-year-old self could invent such precious company. They fulfilled my needs for companionship then, and maybe they fulfil my needs for creativity today.