While mental health is rife throughout society, much of the narrative is around personal accounts of the diagnosed individual rather than what it’s like for their family members. As a child of a mother who suffered from bipolar disorder, it was challenging and oftentimes traumatic.

One of my biggest fears in life is turning into my mother.

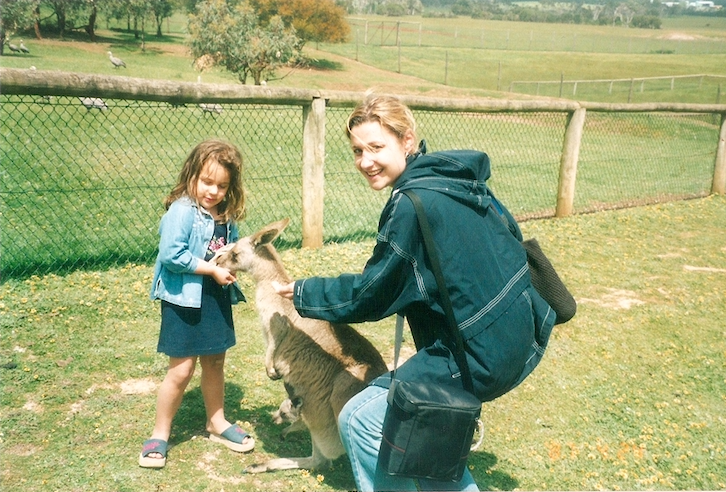

This may seem harsh, but the reality is I have two mothers in the same body. Two mothers who wear the same face but have entirely different personalities, and with whom I have entirely different relationships.

When I was 15, I was confronted with the knowledge that my mum’s erratic behaviour and quick ability to switch between emotions wasn’t considered normal but born of bipolar disease.

Healthline describes bipolar disorder as “a mental illness marked by extreme shifts in mood”, but it is so much more than that. No one has said worse things about me than my mum during her episodes.

Growing up with a parent who suffers with mental health problems is hard work.

It is widely underestimated how much a mental health disorder effects the diagnosed individual and consumes all facets of their lives from support networks, to relationships and even employment.

It has been scientifically proven that an individual’s relationship with their mother is one of the most important bonds one can form in their lifetime. All future relationships hinge on this dynamic and that is where I have struggled for years.

My mother’s mental health has tested our relationship time and again, to the point I have almost ceased our relationship entirely. It’s challenging for many people to imagine that such a universal bond can be threatened and hurt by an uncontrollable part of someone.

I love my mum, I really do, but there’s only so much hurt a person can take from someone so important to them before they begin to shut off.

My earliest recollection of being able to identify her symptoms was during high school, a time already rife with the difficulty of adolescence. When she experienced a manic episode, it was like she was taking upper drugs. She could exercise at the pace of professional athletes, she could socialise into the night, she had no regard for anything other than following where that high might take her.

On the flip side, she would experience depressive lows where she wouldn’t be able to leave her bed for weeks, refused to speak to anyone, her mere form devoid of any semblance of happiness. I didn’t understand at first but over time this pattern does become normal, the hardest thing is realising that the unmedicated version of that person is entirely different from their healthy selves.

I had seen and heard the way familial mental health issues has affected families but to me… I was fine? I had friends, excellent grades, successful sporting career and had a healthy relationship with food. From high school to university I didn’t stop, I threw myself into work, social commitments, work and pretty much anything that would keep me occupied.

Now I realise that it was from the time I was 14, I subconsciously decided that I wouldn’t trust anyone else to take care of me, I had to be emotionally independent.

According to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, “It is estimated that 21-23% Australian children live in families with a parent who has mental illness.”

When you think about how much of the population that actually is raising a generation, the figures can become quite alarming.

To say that my mum’s mental health issues have profoundly affected my life, relationships and attachments is an understatement.

As humans we mimic our parents, we deal with situations in a way we have seen our parents do. Yes, we are our own individual, but it is the environment we grow up in that we relate to the most. I began to mimic some of my mother’s behaviour.

Oscillating between emotions was overwhelming, I experienced a dichotomy of emotion on a daily basis that I would internalise. Being okay and then not being okay within the flick of a switch was as easy as breathing. Traumatic stuff didn’t affect me, small things did. A failed personal issue affected me so much more than failing other people.

To me, for a time, having a mental health issue meant that you were weak minded; you weren’t strong enough to deal with the pressures of everyday life.

I never understood the impact on my own life until I started to notice a reoccurring pattern in my own behaviour. It was then I sought help.

Seeing a therapist is when I realised that I, indeed, have toxic traits which jeopardise my experiences. If I felt the slightest bit abandoned, I would switch off and immediately shut it down for fear of being hurt. I wasn’t able to trust people when they would say nice things because in my mind, if my mother could say the best then worst things about me, what’s to stop someone else.

Ironically, I was arrogant and condescending when it came to understanding mental disorders because I had accomplished so much when living in a dysfunctional household. I always had a guard up so when people do leave it doesn’t hurt as much.

I realised that I needed to work on this. I couldn’t live my life scared of emotion, rejection and hurt. It is our feelings that make life worth living.

Every day I try to take a small step to bring down these walls. I’m sick of being worried and I’m tired of being stressed.

For people who experience similar struggles, I’ve found that the best medicine is to talk, communicate and listen.

Despite how far I’ve come, there will always be a small part of me terrified of turning into something I can’t control, because it is that control that has held me together for so many years.